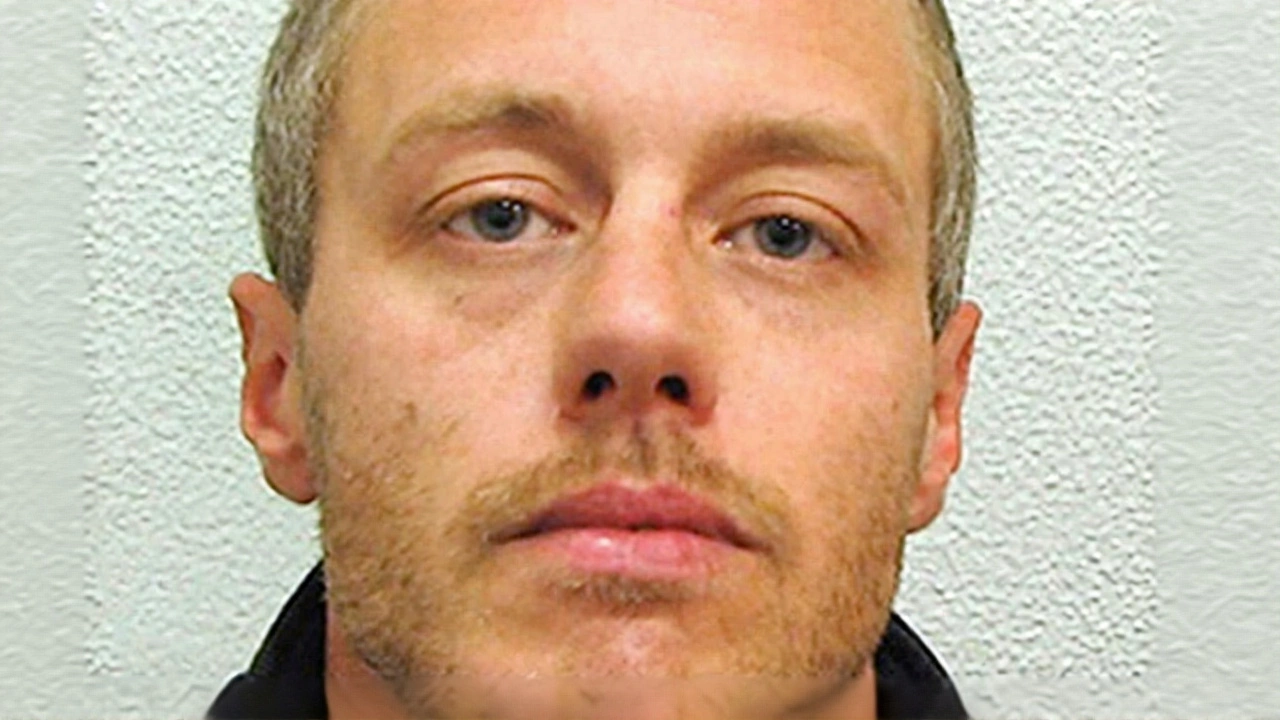

When David Norris, a 49‑year‑old former convict, appeared before a public Parole Board hearing in October 2025, the nation held its breath. The hearing, held via video link from a prison wing in Kent, marked Norris’s first bid for release after serving more than three decades for the racially‑motivated murder of Stephen Lawrence on 22 April 1993 in Eltham, south‑east London.

In a tremulous statement, the former teenager‑aged offender begged Lawrence’s family for forgiveness, yet stubbornly refused to name the other men he claims took part in the attack. "That murder 32 years ago should never have happened. I am totally disgusted with myself and my part in his murder," Norris said, his greying hair barely visible behind the screen.

Background of the Stephen Lawrence case

The murder of Stephen Lawrence, an 18‑year‑old black student, shocked Britain and exposed deep‑seated racism within the Metropolitan Police. Two weeks after the killing, police arrested a gang of up to six youths, but only David Norris and Gary Dobson were ultimately convicted at the Old Bailey in January 2012. The trial hinged on minute forensic traces – a strand of hair and a smudge of blood – that newer DNA techniques uncovered.

Both Norris and Dobson received life sentences with a minimum term of 14 years and three months. The original five suspects identified by witnesses and anonymous tips were Norris, Dobson, brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt, and Luke Knight. The Acourt brothers and Knight have never been charged, and their whereabouts remain unknown.

Norris’ first parole hearing: what happened

The Parole Board, an independent body that reviews life‑sentence cases, scheduled Norris’s oral hearing for 1 May 2025. At Norris’s request, the date was pushed back, and a public hearing was later secured after a media application on 23 January 2025, citing the case’s historic significance.

During the October hearing, Norris admitted for the first time that he had punched Stephen Lawrence during the “unprovoked racist assault,” but he insisted he never handled a knife. "I punched him, I tried to punch him twice, but I didn’t stab him," he said, describing the attack as an “impulse reaction” that lasted “10 seconds or less.” He argued that naming his accomplices would endanger his own family, stating, "In an ideal world I could tell them the whole truth, but it would pose a risk to me and my family."

The board noted his remorse – he had written over 550 letters to victims and families while incarcerated – but also recorded his refusal to cooperate with police investigations that remain open.

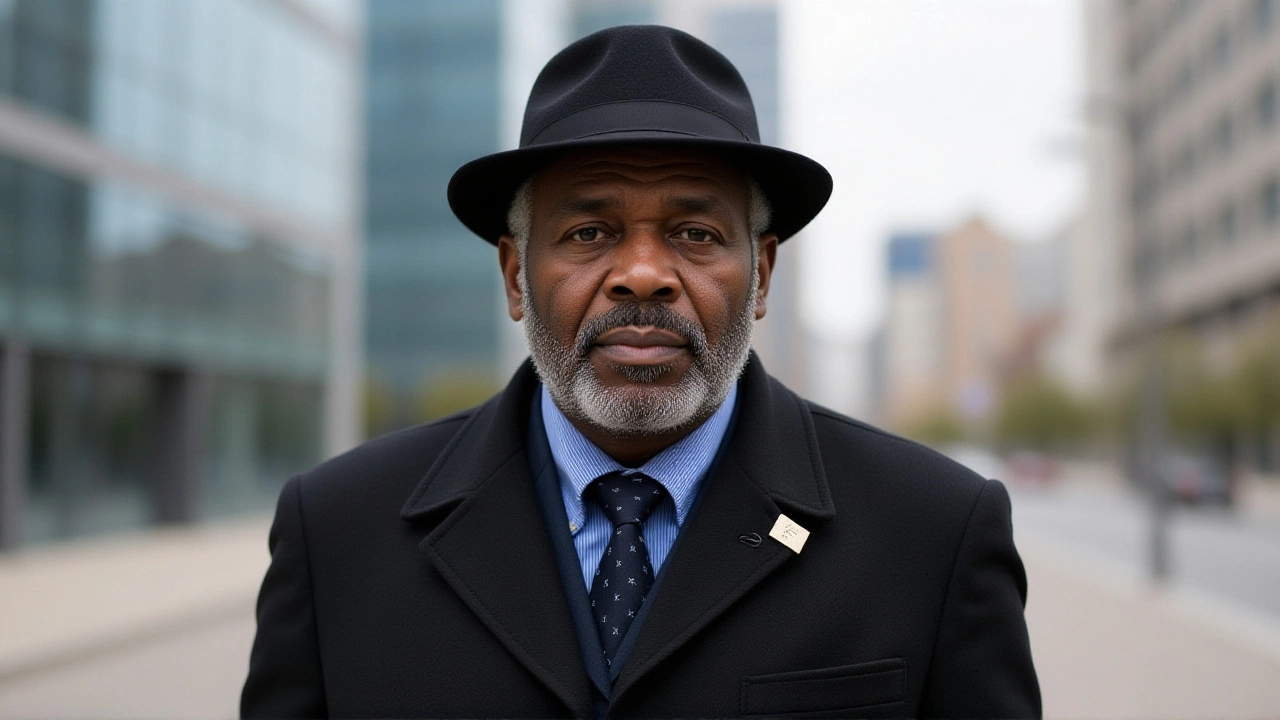

Family and public reactions

Lawrence’s father, Neville Lawrence, has been vocal since the 1999 public inquiry that condemned the police as institutionally racist. "It’s important for me because of what these people have done," Neville said at a recent press conference. "They ruined my life. There’s no way I can even start to think that he should be allowed to walk free unless he tells us who else was involved."

Across social media, opinions split. Some users argued that genuine remorse should outweigh silence, while others echoed Neville’s stance, insisting that accountability for the whole gang is a prerequisite for any release.

Legal and institutional context

The case sits at the crossroads of two long‑running debates: whether parole decisions should hinge solely on an inmate’s behaviour in prison, and whether there’s a moral duty to disclose co‑perpetrators in unresolved murders. Legal scholars such as Professor Emma Tomlinson of King's College London note, "The Parole Board can consider cooperation with law enforcement as a factor, but there is no statutory requirement for a convict to betray accomplices."

Meanwhile, the Metropolitan Police continues to face scrutiny over the original investigation, which was marred by alleged corruption linked to Norris’s father, Clifford Norris, a known drug dealer.

Implications for future parole decisions

If the board recommends release, it could set a precedent for other high‑profile cases where co‑offenders remain at large. Critics warn that leniency without full disclosure may undermine public confidence in the justice system. Supporters argue that staying in prison for 32 years, combined with a demonstrated transformation, should be enough.

Whatever the outcome, the hearing has reignited calls for a fresh inquiry into the unsolved aspects of Stephen Lawrence’s murder, and for a statutory “truth‑telling” provision that would compel convicted killers to reveal accomplices.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why is the Parole Board considering cooperation with police as part of Norris’s release?

The Board weighs any evidence that an inmate is helping to resolve outstanding crimes. Though not a legal requirement, cooperation signals genuine remorse and can lessen the risk of re‑offending, especially in cases where other suspects remain free.

What impact would Norris’s release have on Stephen Lawrence’s family?

Neville Lawrence has repeatedly said any parole would feel like a second blow. The family still seeks answers about the other attackers; releasing Norris without full disclosure could reopen old wounds and fuel a sense of injustice.

How many people were originally suspected of the murder?

Police initially identified up to six youths. Only Norris and Dobson have been convicted; the Acourt brothers and Luke Knight remain uncharged, and their whereabouts are unknown.

What reforms have been made to the Metropolitan Police since the 1999 inquiry?

The inquiry led to the creation of the Independent Office for Police Conduct, mandatory diversity training, and a new “stop and search” policy. However, critics argue systemic bias persists, pointing to the Lawrence case as a benchmark for change.

When will the Parole Board announce its decision on Norris?

The Board typically issues its ruling within six weeks of the hearing. In Norris’s case, a decision is expected by late November 2025, though a formal statement may be delayed if further investigation is required.