A star landlord, a £50,000 claim and a line he says he might draw

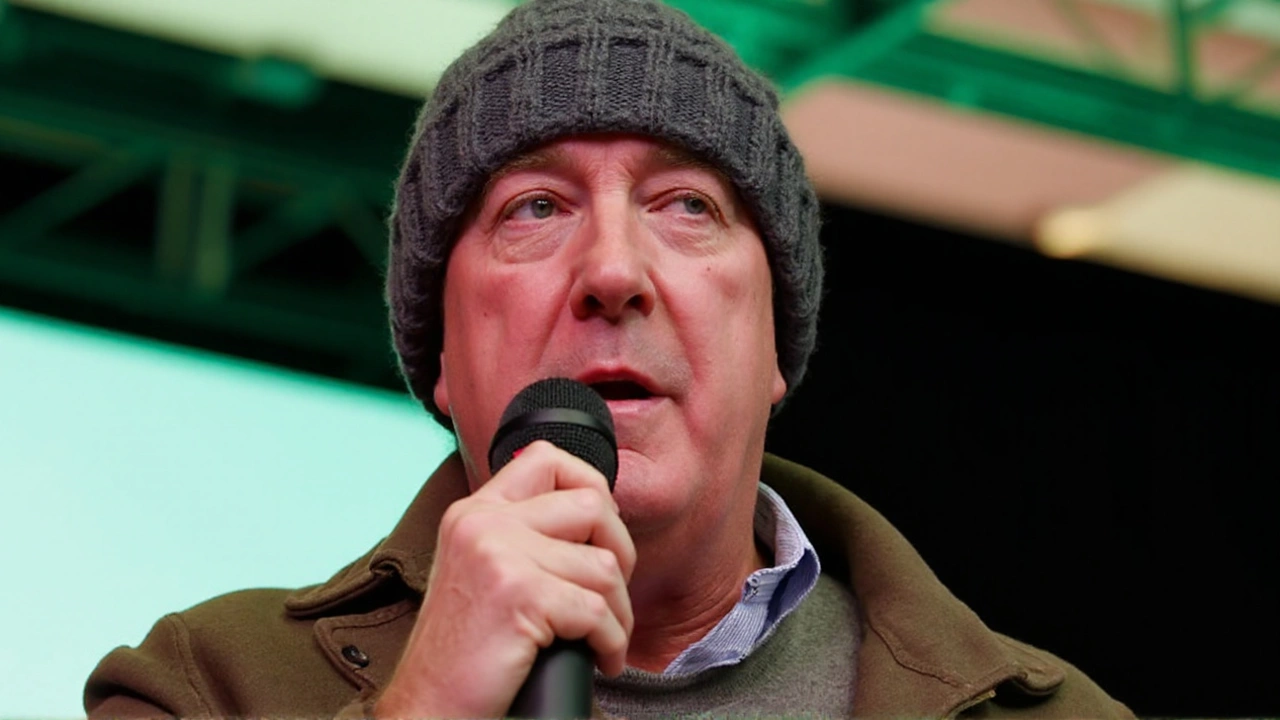

Jeremy Clarkson says he is weighing up a ban on diners with food intolerances at his Oxfordshire pub after what he describes as a £50,000 scam attempt. Writing in his newspaper column, the broadcaster called it part of a wider “fraud epidemic” hitting pubs and restaurants, and said his team is now spending time unpicking claims that arrive after customers have left.

One case stuck with him: a woman allegedly said she was served beer instead of cider, that it aggravated her gluten intolerance and ruined her trip. She then sought damages. Clarkson says he pulled CCTV to challenge the account, a sign of how seriously operators now treat post-visit demands for cash. He insists he won’t pay out lightly, but admits the process drags staff away from, well, running a pub.

He doesn’t pretend a ban would be easy—or smart. He calls it “commercial suicide,” yet says repeat claims from what he dubs “food tolerance enthusiasts” have worn him down. He says the compensation demands tend to land only after people have left the premises, which makes evidence gathering slow and awkward. And when the number is £50,000, mistakes can be expensive either way.

Beyond claims, he says running The Farmer’s Dog is “harder than anything,” even compared with his farming life. He has insisted on using British-only ingredients, and says that choice means the pub loses roughly £10 on each customer who eats there. In a trade where margins are paper-thin even in good times, that’s a hit he notices on every plate.

He also describes the less glamorous side of owning a pub: damaged fixtures, the odd bust-up between drinkers, and the hours swallowed by troubleshooting. Add maintenance, rota gaps and supplier headaches, and his celebrity doesn’t buy him an easier shift—only a busier one.

The most chilling blow didn’t come through the door, though. Clarkson says cybercriminals hacked the pub’s systems, costing him £27,000. He claims the attackers were the same group that targeted high-profile UK brands like Jaguar and M&S. It’s a reminder that even small hospitality businesses now sit on enough data—and enough payment flow—to tempt serious criminals.

Where customer rights meet risk: the industry’s knife-edge

That talk of banning people with food intolerances lands in tricky territory. In UK law, there’s a line between an intolerance and a medically diagnosed allergy or condition. Coeliac disease, for example, is widely treated as a disability in many settings, which brings protection under the Equality Act 2010. A blanket refusal to serve could invite legal and reputational trouble, especially if it sweeps up people with allergies who need safe options to eat out.

There’s also the practical side. UK food law demands clear allergen information and careful handling to avoid cross-contamination. After “Natasha’s Law” arrived in 2021, operators have been expected to go further on labeling for pre-packed foods—while pubs still must communicate allergens accurately and train staff to respond to specific requests. Most venues now keep allergen matrices in the kitchen, log ingredient swaps and note verbal checks at the table, because paperwork can be the difference between a solved complaint and a costly dispute.

Clarkson’s gripe is about alleged abuse of that system: claims that appear after the fact, framed as urgent and high-value, when staff have no chance to investigate in the moment. Hospitality owners say that pattern has become familiar, echoing the “holiday sickness” wave that hit travel firms a few years back—lots of claims, hard-to-prove harm, and insurers caught in the middle. The response has been to tighten processes: timestamped service notes, more cameras, and a clear escalation path when someone reports a reaction on site.

Even then, fighting a claim isn’t simple. Card chargebacks, letters from no-win-no-fee representatives and social media pressure can all push a venue to settle fast. That’s why operators document everything: what was ordered, what was served, what was said, substitutions made, and who handled the table. If a guest reports a suspected reaction before leaving, most pubs now move to a playbook—check ingredients, offer medical help, save samples, log statements from staff and the party, and inform insurers promptly.

Clarkson’s separate decision to stick to British produce adds another layer. Buying domestic can mean higher costs for meat, dairy and seasonal veg, which the industry has felt more sharply since energy spikes and supply disruptions. He’s effectively absorbing that difference on each plate, hoping the brand and loyalty cover the gap. When claims, property damage and a cyberattack show up on top, the sums get ugly fast.

Could he actually bar people who disclose intolerances? It’s hard to see how that works in practice. Many bookings arrive with notes about gluten-free or dairy-free needs. Staff check dishes, chefs adjust, and most services pass without incident. A hard ban would likely push away entire groups dining with one person who has a dietary requirement. It would also run into serious ethical questions and—depending on the case—potential legal ones.

More likely, he reaches for controls rather than a wall: stricter allergen briefings at the door, clearer menu wording, extra checks before serving, and a firm policy for complaints made weeks after a visit. Insurers often advise requiring contemporaneous reporting of an incident, and documenting the response in detail. That doesn’t block genuine claims; it filters out those that can’t clear basic evidence tests.

The cyber angle won’t be a quick fix either. Small venues are now expected to guard everything from booking platforms to point-of-sale systems. Two-factor authentication, limited administrator access, and fast patching are becoming standard. It’s not glamorous work, but one breach can wipe out months of profit—exactly the kind of hit Clarkson says he took.

Strip away the fame and it’s a very familiar pub story in 2024: higher input costs, tougher compliance, staff shortages, and a steady stream of left-field risks—from spurious demands to real hacks. Celebrity can fill the dining room, sure, but it also raises the stakes when something goes wrong. Clarkson may not actually ban anyone, but the fact he’s even thinking about it tells you how brittle the numbers feel behind the bar right now.